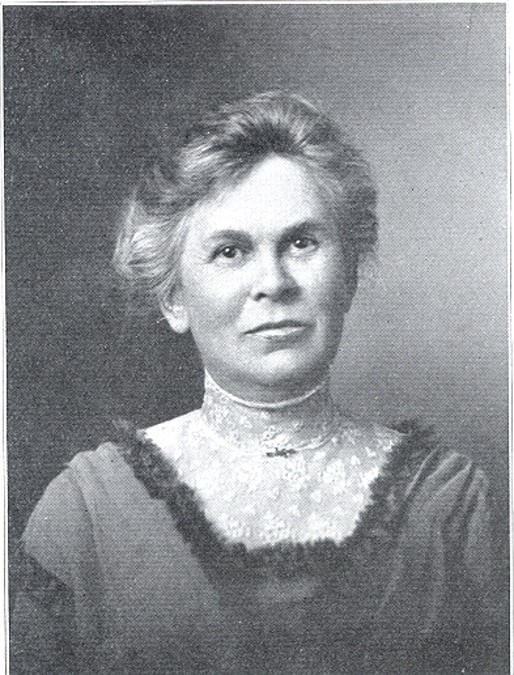

About Deborah N. Morton

Deborah Nichols Morton was associated with Westbrook Seminary and Junior College for over 60 years, and her entire life of service to education and to civic and cultural affairs centered around her Westbrook experience.

Family Background

Born in 1857 to Leander Morton and Deborah Nichols McIntyre, Deborah Morton was a native of Round Pond, Maine. She grew up in a community “reborn in the wave of commerce and invention which swept the eastern seaboard after the Civil War.”

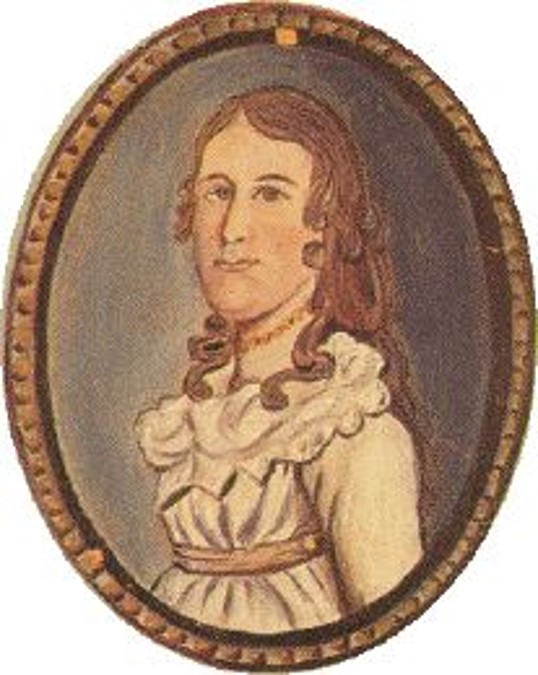

Deborah Morton’s great-great-grandparents, Hannah and Joshua Bradford, were scalped by Indians in 1758, in Friendship, across the bay from Round Pond. In 1780 their niece, Deborah Sampson, became a Revolutionary War soldier by joining the Continental forces under the name of Private Robert Shurtleff.

In 1875, Deborah Morton’s father chartered the Odd Fellow’s lodge and recruited the town’s new workers into the social life of the community. Her mother taught school in Bristol for fifty years. Together her parents were founders of the Little Brown Church that was established as a “union meeting house” open to all.

Education and Early Career

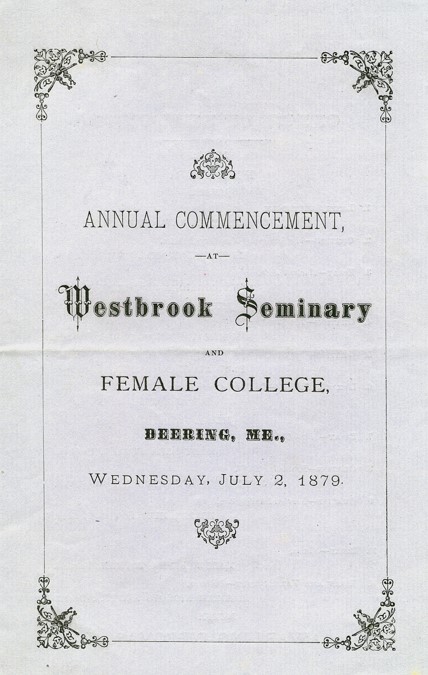

Deborah Morton entered Westbrook Seminary and Female College as a student in 1876 and graduated as valedictorian of the class of 1879. She then began teaching in her home town of Round Pond in Bristol.

In 1884 Miss Morton was invited to fill a vacancy in the faculty of Westbrook Seminary. The next year she was appointed teacher of grammar, rhetoric, and algebra, and was given charge of the girls. In 1886 she became Preceptress and teacher of French and rhetoric.

During the next two years Miss Morton studied French privately and in the summers attended Sauveur College of Languages. In 1888 a year’s leave of absence was granted for study in France and Germany. She spent 1911-12 studying at Boston University.

Preceptress and Reformer

An educator in the broadest sense, Deborah Morton’s gift was her extraordinary ability to stimulate the minds of others. She had an adventurous spirit and was a born questioner.

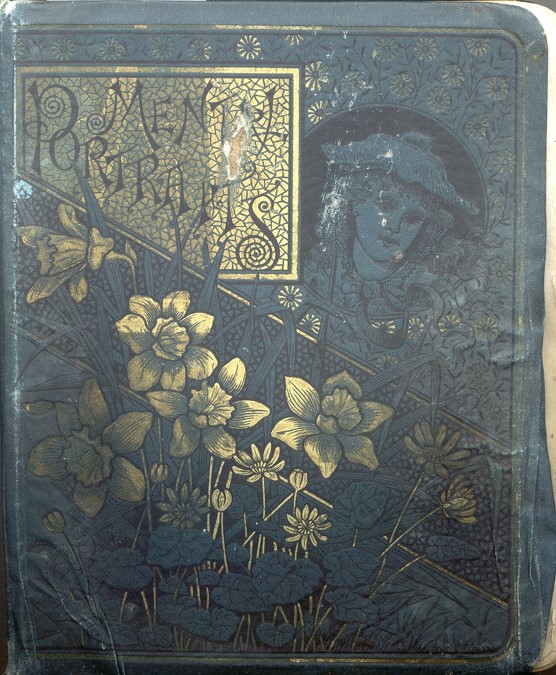

Deborah Morton’s spirit is captured in an entry she made in a friend’s “Mental Portrait Album” in 1892: Asked to name her “idea of real misery,” she wrote “Dependence.” Asked to state the “fault for which she had the most toleration,” she answered, “too much zeal”; “apathy” was the fault she scorned. Asked to name the single locality she would like to visit above all others, she wrote “Utopia”; for her traveling companion she chose “a well-filled purse.”

Deborah Morton’s intellectual pursuits led her far afield. Politics, history, art, languages, literature, the growth of social institutions — all were subjects of inquiry for her restless mind.

A photograph of Deborah Morton at Westbrook Seminary, pouring tea for faculty in 1896/97 captures something of the charm and directness of her manner. As preceptress in 1886 she had been called upon to resolve the “Great Strike of the Young Ladies” when eight rebels had demanded the right to travel unescorted beyond campus grounds. Her support went to the rebel side. And in the 1890s she became a firm advocate of dress reform through which the young ladies sought release from the confinement of long skirts and petticoats.

Within the 1913-1914 Westbrook Seminary Catalogue we read, “Miss Deborah N. Morton, L.A., needs no introduction to people familiar with the educational progress of Maine. . . . [S]he is the Dean of Modern Language teachers in Maine.”

In 1917 Miss Morton left Westbrook Seminary believing she would like to be free to engage in club and war activities. At that time she was president of the Women’s Literary Union, and was active in the Y.W.C.A. war council. Five years later there was general rejoicing in the school and among alumni when Miss Morton returned to the Seminary to continue teaching French.

Travels

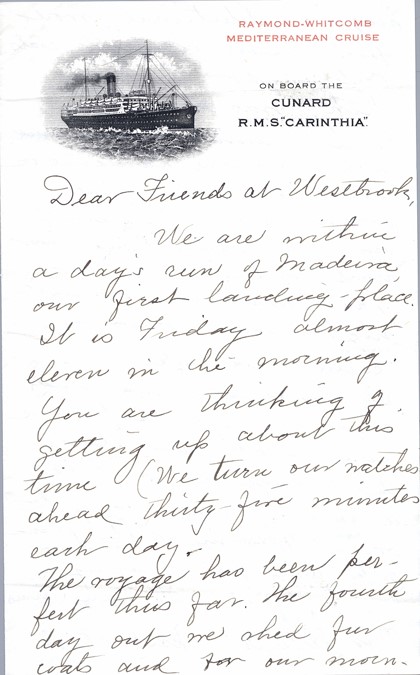

Miss Morton’s summer vacations were spent in study at Middlebury College, the University of Vermont, and the Sorbonne in Paris. Other summers during her busy teaching career were taken up with organizing and conducting parties to Europe, acting as interpreter in French and German. Altogether during her association with Westbrook Seminary and Junior College she made fourteen trips to Europe and the Near East.

For Deborah Morton, who never married, Westbrook became her family. Letters from abroad to her “friends at Westbrook” read like letters to intimate companions. They are full of “news,” commentary, and asides on the rituals of transatlantic travel.

“’The world is full of temples and of towers,’ begins a poem dedicated to Deborah Morton by an alumna in 1930. ‘And she has known them, yet returns to ours.’ Like other nineteenth-century travelers, [Miss Morton] provided the Portland community with news of a larger world – and did so well into the 1930s when she is remembered for her solemn assessment of Hitler’s rise to power in Germany at a time when most people dismissed the Fuhrer as an upstart. . . . And scholars who travel as far and wide as Deborah Morton did rarely come home again.”

Westbrook Seminary as Home

Deborah Morton’s genuine pride in Westbrook and in the progressive traditions of its free-thinking Universalist founders is reflected in her 1931 commencement address delivered during the Depression, one-hundred years after the founding of Westbrook Seminary in 1831: “Our teachers in every department are trained for their special work. Our buildings are in order . . . . We lay no claim to the elegances of ultra-fashionable schools, but we do claim that for all the essentials of a healthy, modern school we are equipped to compete with the best.”

“The depth of Deborah Morton’s personal attachment to Westbrook is captured in a letter she wrote . . .

In 1937; she was eighty and preparing to leave her rooms in Goddard Hall. . . . The college had just taken on twenty-one desperately needed new students and she had offered her quarters if two more showed up. ‘I dread the thought of disposing of my things and living in a couple of trunks at a hotel . . . of tearing myself away from the home of a lifetime,” she wrote, ‘but my conscience may not permit me to do otherwise. . . . Old women do not like change,’ . . .

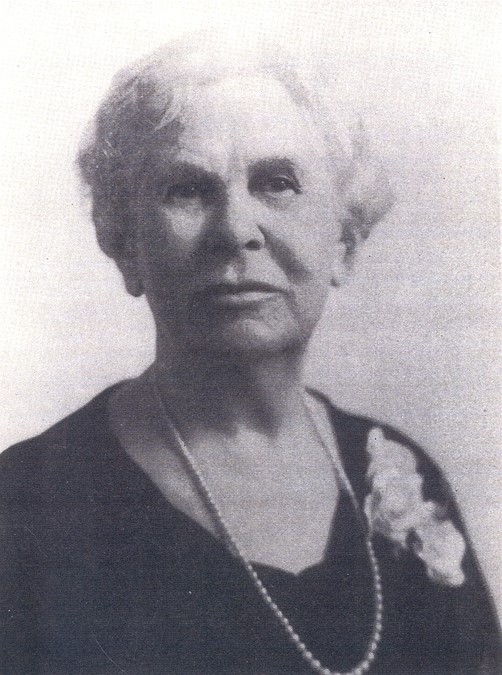

Final Years

“As it happened, Morton fared quite well on her own. The routines of the solitary thinker’s life—the morning letters, the news, rest and reflection, the social hour, a reading after dinner, and discussion—all these continued, first at the Hotel Eastland, then at the Eunice Frye Home. In 1942 she wrote that she was not ‘rusting out.’ She was eighty-five and still reading avidly. ‘To vary the program, I take a couple of hours of club life when I think the lecture is worth it.’”

Deborah Nichols Morton died at the age of ninety in 1947. She was buried at Round Pond’s Maple Cemetery. She was a teacher, preceptress, educator, lecturer and reformer, serving in the vanguard of women who fought for equal rights on the social, political and economic levels.

The Deborah Morton Society

The Deborah Morton Awards were initiated at Westbrook College in 1961 to honor those women who have, in the manner of Deborah Morton, achieved high distinction in their careers and public service, or whose leadership in civic, cultural, or social causes have been exceptional.