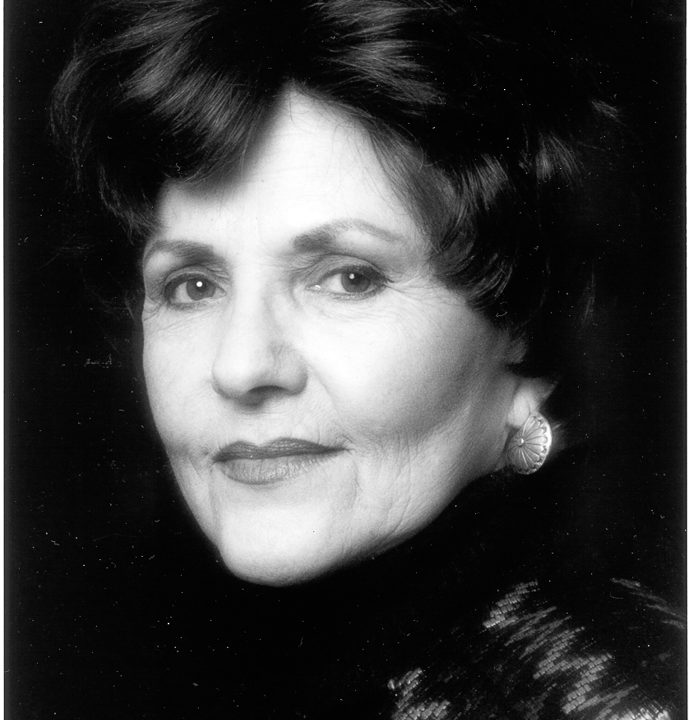

Perdita Huston: Global Passion, Local Action

Maine native Perdita Huston spent her professional life advocating for sustainable development and sound family planning worldwide. She spent a number of years living in northern Africa and France before settling in the Washington, D.C. area where she directed programs for the American Revolution Bicentennial Administration and was involved with many organizations and delegations, including several United Nations agencies, the Peace Corps, and the American Revolution Bicentennial Administration, and as director of Public Affairs for the International Planned Parenthood Federation. She published several books dealing with state of families and the status of women worldwide.

Huston’s collection documents her professional life, beginning with her journalism work with Time-Life, Inc. in Algeria until her final work on the Global Family Project in the late 1990s. Included are research notes, interview transcripts, drafts of her writing projects, correspondence from throughout her career, and material on organizations and conferences she was involved with. Also included are clippings of published articles by and about Huston.

Early Life, 1936-1956: Portland, Maine; Newton, Massachusetts; Tuckahoe, New York

Perdita Huston was born on May 2, 1936 in Portland, Maine, to Thomas Augustus Huston and Marion “Mimi” Althea Brooks Huston. The family lived in Auburn, Maine, but moved to Portland soon after Perdita’s birth. For the first 9 years of her formal education, Perdita attended Portland Public Schools.

By 1950, her father was transferred and the family moved to Newton, Massachusetts. After finishing the eighth grade in Newton, Perdita returned to Maine to attend Gould Academy, a private college-preparatory day and boarding school in Bethel. An active member of the Class of 1954, Perdita was on the staff of the 1952 Academy Herald, a singer in the Varsity Glee Club, and a reporter for the newspaper, The Blue and Gold.

When the family was transferred to Tuckahoe, New York, she enrolled in the Bronxville High School for the 11th grade and Tuckahoe High School for the 12th. There she participated in intramural basketball and Glee Club, was news editor of the monthly Tigers Roar school newspaper, secretary of the Teen Canteen and of the Honor Society, won Miss Eastchester 1954, and was voted “Best Personality” by her classmates. After graduation, she spent the academic year 1954-55 at the University of Colorado in Boulder where she began to lay the groundwork for her future career by taking French, English and sociology courses. Troubled by McCarthyism and its repressive spirit, she left the United States in 1956 for France before finishing college.

Education, 1956-1958: Grenoble and Paris, France

Once in France, Huston enrolled in the Université de Grenoble and received a certificate in 1956.

In October 1957, Huston married a Tunisian-born French medical student, Yves Champey, and their first daughter, Françoise, was born in Paris on March 31, 1958. That same year, Huston completed a journalism degree at the École Supérieure de Journalisme in Paris and then earned her BA degree in sociology and international relations at the École des Hautes Études Sociales, Paris.

Medical Social Work, Research, Writing, 1958-1966: Algeria and Tunisia

In 1960 the French government drafted Huston’s husband, Dr. Yves Champey, and appointed him physician in charge of a large segment of the population in Aïn Mokra in the most dangerous Algerian region of the Constantinois. Accompanied by Huston and their daughter Françoise, he supported French troops who were fighting against the warriors for independence. With Huston’s support he also provided illegal medical care to the fellagha, considered terrorists by the French, and called “Algerian freedom fighters” by the English-speaking press.

Huston was pregnant with their second child at the time. Not wanting the baby to be born into a war-torn country, Huston crossed the border into Tunisia with Françoise. There her second daughter, Jeanne Marie, was born on June 24, 1961. Huston stayed in Tunisia and worked for the Tunisian Ministries of Information and Foreign Affairs, assisting as secretary, translator, and English communications officer until the French-Algerian War ended in 1962.

While in Algeria, Huston began her life-long advocacy for people living in developing countries, especially rural women. After the country’s 1962 independence, Huston and Champey returned to Algeria to assist in setting up a comprehensive public health care system. Perdita became a medical social worker, distributing food, helping to deliver babies and writing for the illiterate. Additionally, Huston was a research assistant for The New Yorker (1963), consular foreign affairs officer for the UN in Algiers, and a freelance writer (1963-66).

TIME-LIFE, Inc., 1966-1971: Paris, France

After separating from her first husband, Huston returned to Paris with her daughters Françoise and Jeanne-Marie. There she worked as a professional journalist for Time-Life, Inc., researching and writing freelance articles about situations in North Africa and other subjects.

In 1967, Huston discovered that she had tuberculosis and underwent treatment at a French Alpine clinic for nearly a year, leaving her daughters with their grandmother Champey. She then returned to Paris, and her work at Time-Life, Inc.

When a fire in the Time-Life building claimed the life of her boss, Huston took over as Director of Corporate Public Affairs in French-speaking countries. This position provided her with a lavish expense account, as she was responsible for hosting numerous dignitaries and other famous visitors. Among these was Life photographer Enrico Sarsini, with whom she developed a relationship. He was known for his coverage of Vietnam, Iran, and the funeral of Martin Luther King. Huston held the post at Time-Life, Inc. until she left France in 1971.

American Revolution Bicentennial Commission, 1971-1976: Washington, DC

After seventeen years in North Africa and Paris, Huston, who returned to her maiden name, returned to the USA and settled in Washington, DC.

Hugh Sidey of Time-Life, Inc. facilitated contact with the Nixon administration to help Huston find employment upon return, and with the help of William Safire, then a Nixon White House senior speech writer, she became Director of the Women and Minorities Program for the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission from 1971 to 1974. She went on to serve as director of the Festival USA and Horizons ‘76 programs from 1974 to 1976. To accomplish all of this, she organized her own coalition of professional, educated women leaders.

In 1972 Huston married Marcel Dioennet, a physician she had met in Paris who established orphanages for Vietnamese polio victims. Their son Pierre-Marc was born March 21, 1973. In 1975, Huston helped Diennet publish his book, Children of Phu-My. The couple divorced in Paris on May 17, 1976. Huston retained custody of their son.

North Africa, Near East, Asia, Pacific (NANEAP) Peace Corps, 1978-1981

Huston served as the first female regional director of the Peace Corps from 1978-1981; she was responsible for the administration and management of programs in North Africa, Near East, Asia, Pacific (NANEAP). She supervised overseas staff of 225 in 18 countries, 2,000 volunteers and a headquarters regional staff of 26.

In 1981, she became Associate Director for Development Education. As senior confidential advisor to the Director of the Peace Corps, she planned and implemented the agency’s nationwide development education programs. To mark the 20th anniversary of the Peace Corps, Huston spearheaded a global study of how the agency was perceived around the world, recording interviews with approximately 20 state officials.

Book Publications: 1978- 1979

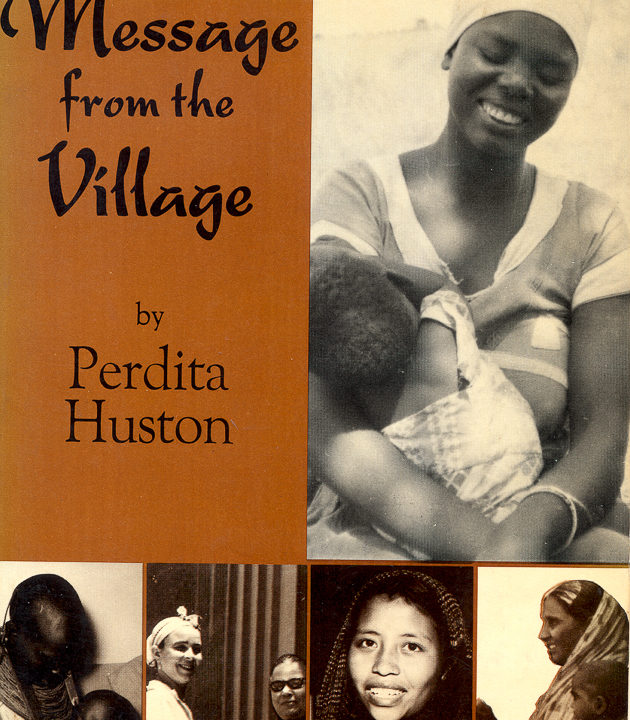

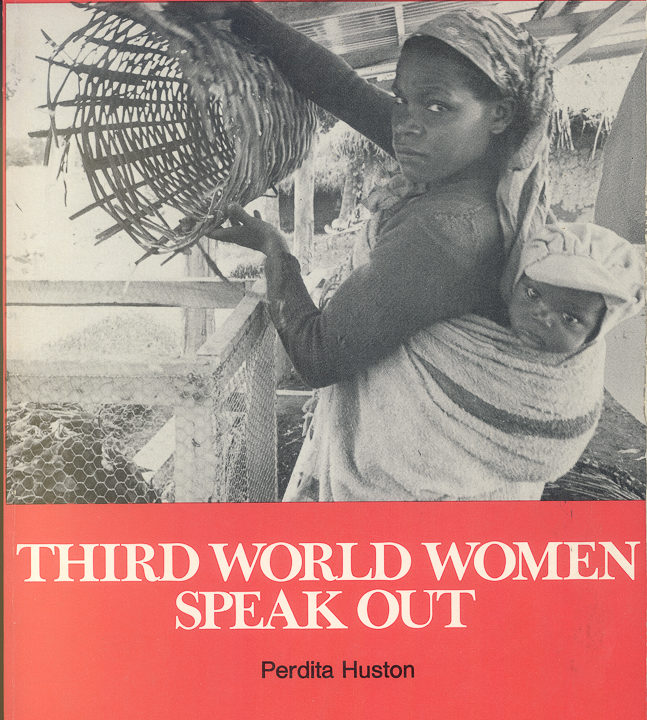

Huston’s publications concern the worldwide state of families and status of women. She researched her first two books, Message from the Village (Epoch B Foundation, 1978) and Third World Women Speak Out: Interviews in Six Countries (Praeger, 1979), as she traveled through developing countries—Tunisia, Egypt, Sudan, Kenya, Sri Lanka, and Mexico. In these books, Huston provides a space for these little-heard women to speak about their political, economic and social concerns.

Message from The Village

Her dedication of Message from the Village reads, “For those whose words are the basis of this book, with admiration and respect,” and her introduction concludes, “Sharing each others’ experiences, we become help-mates and friends, learning from each other. They were reaching out for knowledge. But so was I. I left each woman with a sense of regret. There was never enough time…The message they send is urgent.”

Third World Women Speak Out

Huston’s second book, Third World Women Speak Out, was published in 1979. Richard C. Holbrooke wrote of this book: “ …[I]t was, so far as I could tell, the first book that documented—in women’s own words—the unexpected negative consequences that even a good development process had on third world women. . . . Perdita’s book was an absolute revelation, showing, among other things, that foreign aid in a developing economy often increased the inequality between men and women, especially in the agricultural sector.” (from the foreword to Families As We Are, 2001, p. x)

Wheaton College, and Consultant on Public Policy and Public Affairs, 1981-1985: Norton, Massachusetts and Washington, DC

Huston was awarded an honorary doctorate from Wheaton College in Norton, Massachusetts in 1980. Lecturing on international relations and serving as an advisor to foreign students, she held the post of Scholar-in-Residence at Wheaton from 1981 to 1983.

In 1981, Huston addressed the “Planet Without a Plan?” Conference for Youth on Population and Development held at Lincoln Cathedral by the organization Population Concern of London, England.

In 1982, while a member of the board of Amnesty International, Huston traveled with a group of twelve women to Israel, Lebanon, Jordan and the West Bank. The trip was sponsored by the Middle East Council of Churches and the Palestine Human Rights Campaign. This trip served as a study tour to understand the conflicts in the region — their roots and possibilities for a just resolution.

From 1983 to 1985, Huston consulted with international and national clients in the public and private sectors on public policy and public affairs. The organizations with which she worked include:

- The Jordan Society, organized to improve US-Arab relations.

- Committee on African Development Strategies, a joint project of the Council on Foreign Relations and the Overseas Development Council.

- InterAction Council, a group of 30 former heads of government that sought to influence international decision-making through position papers and high-level contacts.

- Sandra Nichols Productions, LTD., producer of the documentary film African Recovery at the request of the United Nations Department of Public Information.

- Overseas Education Fund International report on the National Consultative Committee for the UN Conference on the Women’s Decade, US Information Agency.

- Refugee Policy Group

- UNICEF

- UN Voluntary Fund for Women

World Conservation Union (IUCN), 1985-1987: Gland, Switzerland

As Coordinator of the Population and Sustainable Development Programme for the World Conservation Union (IUCN), Huston was charged with the creation of a program integrating demographic trends and population policy with natural resource management planning across the range of IUCN activities. She also served as Senior Advisor to IUCN on Women and Natural Resource Management.

International Planned Parenthood Federation, 1987-1990: London, England

In 1988, Huston left the IUCN to become Director of Public Affairs for the International Planned Parenthood Federation. There she was charged with creating a new department to enhance the Federation’s global visibility through publications, media, conference organization and coalition-building.

The IPPF and IUCN worked closely together on population and planetary environmental issues; Huston maintained her connection to the IUCN by serving as a member of the IUCN’s Commission on Education and Training to establish a network among women educators, trainers and communicators. While a part of this commission she served on both the Womens’ Involvement in Environmental Education and Communication subcommittees.

The Global Family Project, 1991-1996: Washington, DC

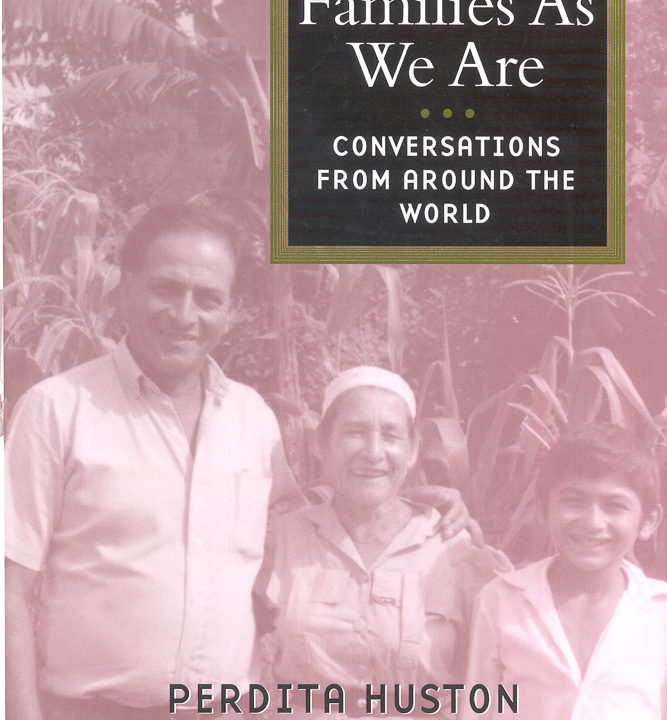

As Director of the Global Family Project from 1991 to 1996, Huston conducted oral history interviews with families in 12 nations funded by UNDP, UNIFEM, UNFPA, UNICEF, and several private foundations. This research led to the publication of her final book, Families As We Are: Conversations From Around the World (Feminist Press, 2001).

Motherhood by Choice, 1992

Huston’s work with the International Planned Parenthood Federation led to her research for, and publication of, a third book, Motherhood By Choice: Pioneers in Women’s Health (The Feminist Press of the City University of New York, 1992). The book recounts the experiences of early family planners in twelve countries: the Dominican Republic, Norway/Sweden, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Egypt, Thailand, Tunisia, Bangladesh, New Zealand, Ghana, Japan and Mali.

The text was also published in London under the title The Right to Choose: Pioneers in Women’s Health & Planning (Earthscan Publications, in association with International Planned Parenthood Federation, 1992).

Peace Corps, 1997-2000: Mali and Bulgaria

Huston served as Peace Corps Country Director for Mali from 1997 to 1999, and for Bulgaria from 1999 to 2000. In Mali, she was responsible for the management of the largest Peace Corps program in Africa, working in Small Enterprise Development (SED), Natural Resource Management (NRM), Agriculture and Gardening (AG), and Community Health and Water/Sanitation. In both positions she trained and supervised hundreds of volunteers and host country staff, and served as liaison with the Malian and Bulgarian governments as well as non-governmental organizations and the diplomatic communities.

Families As We Are, 2001

For five years, Huston visited families in eleven countries—Japan, Thailand, Bangladesh, China, Mali, Uganda, Egypt, Jordan, Brazil, El Salvador, and USA—to gather the materials for her final book—Families As We Are: Conversations from Around the World (The Feminist Press at the City University of New York, 2001), the outcome of her Global Family Project. Richard C. Holbrooke commented in his forward to her book:

“…[H]er interviews suggest that the nature and definition of family has evolved in many ways that are not yet fully understood. Deeply traditional in her attachment to the idea of family, Perdita is characteristically open to examining the different forms it takes in the modern world.” (p. x)

Awards and Honors

Throughout her career, Huston participated in local and international conferences concerning women’s rights, sustainable development, and media ethics. She was a regularly featured lecturer on university campuses and in other educational settings. She was also widely recognized for her contributions to the broadening of human rights. She received honorary degrees from Wheaton College (1980) and Southeastern Massachusetts University (1983).

Huston was the first recipient of the Margaret Mead World Citizen Award (1980), given by New Directions, a Citizen’s Lobby for World Security (later WAND: Women’s Action for New Directions / Education Fund). Mary Catherine Bateson, Margaret Mead’s daughter and the dean of faculty at Amherst College, presented the award in absentia to Huston, who was then traveling in Africa as the Regional Director of the Peace Corps.

Her dozens of organizational affiliations include the U.S. Committee for UNICEF (Member, 1981-86), the Jordan Society (Trustee, 1981-87), and Amnesty International (Board of Directors, 1982-87). In a 1989 interview with Rushworth M.Kidder, then of the Christian Science Monitor, Huston emphasized “the moral and social implications of the gap between the developed and the developing world. In particular, she pointed to three qualities most needed to close the gap: a willingness to listen, a rethinking of male-female relationships, and what she calls ‘nature literacy'” (July 12, 1989, p. 12). She visited the White House at least three times, at the invitation of presidents Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton.

Diagnosed with fourth stage ovarian cancer in 2000 while serving as the Peace Corps Country Director in Bulgaria, Huston returned home and died in Silver Spring, MD on December 4, 2001, at the age of 65. The United Nations Association for the National Capital Area created in her honor the Perdita Huston Human Rights Award, which awards a substantial stipend to a young woman engaged in pursuing goals similar to Huston’s.

In 2005, the Perdita Huston Purple Starfish Award was supported by the Lillian M. Berliawsky Charitable Trust and the Maine Women Writers Collection to honor Huston by granting a study fellowship to a woman under 30 who shares Huston’s passion for righting some of the world’s multicultural wrongs.

Exhibit text adapted from biographical sketch of Perdita Huston by Carol F. Kessler.